The evolution of Indonesia’s trade defense mechanism represents a sophisticated synthesis of international treaty obligations and domestic industrial priorities. Since the nation ratified the Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization (WTO) through Law Number 7 of 1994, the Indonesian legal landscape has undergone a systematic transformation to internalize the rigorous standards of the WTO Anti-Dumping Agreement (ADA). This process has not been merely a technical adoption of rules but a strategic legislative journey, shifting from the foundational provisions of the mid-1990s to the highly refined procedural frameworks of the 2020s. At the heart of this development lies a tension between the principles of free trade and the imperative to safeguard domestic industries from “unfair” pricing practices, specifically dumping. Dumping, defined as the importation of goods at an export price lower than their normal value in the country of origin, is viewed within the Indonesian legal system as a market distortion that necessitates corrective state intervention.

The Legislative Foundations of Trade Defense in Indonesia

The constitutional and statutory basis for Indonesia’s anti-dumping regime is anchored in the country’s customs and trade laws. The primary authority for the imposition of anti-dumping duties was first codified in Law Number 10 of 1995 concerning Customs, which provided the government with the legal mandate to levy additional duties on imported goods that cause or threaten to cause material injury to domestic producers. This law was significantly updated by Law Number 17 of 2006, which sought to address emerging complexities in global trade and clarify the administrative procedures for duty imposition. These statutory instruments established that anti-dumping measures are not standard tariffs but remedial tools designed to level the playing field when foreign exporters engage in predatory pricing strategies.

The technical implementation of these broad mandates was initially governed by Government Regulation (PP) Number 34 of 1996. However, as the Indonesian economy became more integrated into global value chains and faced increasing scrutiny from the WTO Dispute Settlement Body, the 1996 regulation was replaced by the more comprehensive Government Regulation Number 34 of 2011 concerning Anti-Dumping Measures, Countervailing Measures, and Trade Safeguard Measures. This 2011 regulation serves as the current procedural bedrock, detailing the requirements for determining dumping margins, the criteria for material injury, and the necessity of establishing a causal relationship between the two. It also provides the legal basis for the Indonesian Anti-Dumping Committee (KADI) to conduct investigations and recommend the imposition of Anti-Dumping Import Duties (BMAD) to the Minister of Finance.

Table 1: Primary Legal Instruments in Indonesia’s Trade Defense Framework

| Regulation | Year | Primary Legal Purpose | WTO Alignment Status |

| Law Number 7 | 1994 | Ratification of WTO Agreement | Foundational Treaty |

| Law Number 10 | 1995 | Basic Customs Authority for Trade Remedies | Statutory Foundation |

| Law Number 17 | 2006 | Modernization of Customs Procedures | Procedural Update |

| GR Number 34 | 2011 | Comprehensive Trade Remedy Procedures | Fully Harmonized |

| Law Number 7 | 2014 | General Trade Law and Economic Sovereignty | Strategic Framework |

| MOTR 33/M-DAG | 2014 | KADI Organizational Restructuring | Institutional Update |

| MOTR 16 | 2025 | New Import Governance and NTM Streamlining | Post-2024 Reform |

The 2011 regulation (GR 34/2011) introduced several critical definitions that align Indonesian practice with Article VI of GATT 1994. It defines “Like Products” as domestically produced goods that are identical or possess characteristics resembling the investigated imported goods. Furthermore, it clarifies the concept of “Domestic Industry” as the collective body of domestic manufacturers of like products, or those whose production accounts for a large proportion of total domestic output. This legal precision is essential for maintaining the legitimacy of investigations, as any deviation from these definitions could lead to a successful challenge at the WTO.

Institutional Architecture: The Role and Mechanics of KADI

The Indonesian Anti-Dumping Committee (Komite Anti Dumping Indonesia, or KADI) serves as the technical vanguard of the nation’s trade defense system. Established as a non-structural body under the Ministry of Trade, KADI is tasked with the dual responsibility of protecting domestic industries and ensuring that investigations adhere to the principles of transparency and objectivity. Its operational mandate was significantly refined through Minister of Trade Regulation Number 33/M-DAG/PER/6/2014, which restructured the committee to enhance its investigative rigor and internal accountability.

KADI’s investigative process is highly formalized, beginning with the receipt of a petition from a domestic industry association or a representative group of producers. For a petition to be accepted, the applicants must represent at least 25 percent of the total domestic production of the like product, and the investigation will only proceed if it is supported by producers whose collective output constitutes more than 50 percent of the total production of those expressing an opinion. This ensures that anti-dumping measures are used to protect an entire industrial sector rather than individual companies.

The Investigative Lifecycle and Evidentiary Standards

A KADI investigation typically follows a structured timeline, beginning with a 12-month period that can be extended to 18 months under exceptional circumstances. The process is initiated by the issuance of a public notice and the distribution of detailed questionnaires to all known interested parties, including foreign exporters, importers, and the governments of the exporting countries. These questionnaires are notoriously comprehensive, requiring the submission of computerized data in specific formats, such as Excel files compatible with American or European standards, and narrative responses in “Arial Narrow” font size 10.

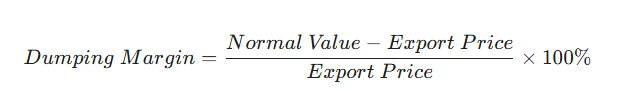

The core of the investigation involves the technical calculation of the dumping margin and the assessment of injury. KADI must determine the “Normal Value” of the product, which is the price paid for the like product in the domestic market of the exporting country. This is then compared to the “Export Price” paid for the goods when sold to the Indonesian market. The dumping margin is expressed by the following LaTeX formula:

In cases where the domestic market price is unavailable or distorted—a situation referred to as a “Particular Market Situation” (PMS)—KADI may use a “Constructed Normal Value”. This involves calculating the actual cost of production in the country of origin plus a reasonable amount for administrative, selling, and general costs (SGA), as well as a profit margin:

Constructed Normal Value = Cost of Production + SGA Expenses + Profit

The determination of injury is equally complex, requiring KADI to analyze volume effects (a significant surge in imports) and price effects (price undercutting or suppression). KADI must also establish a causal link, proving that the material injury suffered by the domestic industry—such as declining profits, reduced market share, or layoffs—is directly attributable to the dumped imports and not to other external factors like shifts in consumer preference or global economic downturns.

Table 2: KADI Investigative Thresholds and WTO Compliance

| Metric | Threshold/Requirement | Legal Source | WTO Consistency |

| De Minimis Margin | < 2% of Export Price | GR 34/2011, Art. 19 | Article 5.8 ADA |

| Negligible Volume | < 3% of Total Imports | GR 34/2011, Art. 19 | Article 5.8 ADA |

| Cumulative Volume | < 7% (when aggregated) | GR 34/2011, Art. 19 | Article 5.8 ADA |

| Standing (Petitioner) | > 25% Total Domestic Production | GR 34/2011, Art. 7 | Article 5.4 ADA |

| Final Support | > 50% of Producers responding | GR 34/2011, Art. 7 | Article 5.4 ADA |

| Duration | 12-18 Months | GR 34/2011, Art. 21 | Article 5.10 ADA |

If an investigation finds that the dumping margin is de minimis (less than 2 percent) or that the volume of imports is negligible (less than 3 percent from a single country), KADI is legally obligated to terminate the investigation immediately. This adherence to international thresholds is a hallmark of Indonesia’s commitment to the rules-based multilateral system.

The Geopolitics of WTO Disputes: Case Studies and Jurisprudential Impact

Indonesia has not only developed its anti-dumping laws internally but has also been a prolific participant in the WTO Dispute Settlement Body (DSB), both as a complainant and a respondent. These disputes have served as a critical laboratory for testing the robustness of Indonesian trade defense instruments and have forced the government to refine its investigative methodologies to withstand international scrutiny.

The Korea Paper Dispute (DS312) and Procedural Transparency

One of the most foundational cases in Indonesia’s trade history was Korea – Anti-Dumping Duties on Imports of Certain Paper from Indonesia (DS312). In this dispute, Indonesia challenged the Korea Trade Commission’s (KTC) imposition of anti-dumping duties on Indonesian paper products. The WTO Panel found that the KTC had acted inconsistently with Article 6.2 of the ADA by failing to provide Indonesian producers, specifically the Sinar Mas Group, with a proper opportunity to comment on the evaluation of injury factors.

Furthermore, the KTC was found to have erred in its use of “facts available,” a provision that allows investigating authorities to use secondary data if exporters do not cooperate. The DS312 ruling was a major victory for Indonesia and reinforced the principle that anti-dumping investigations must be conducted with the highest degree of transparency and due process. This case had a direct ripple effect on the drafting of GR 34/2011, which now includes stricter requirements for KADI to disclose the essential facts under consideration and to provide parties with ample time to defend their interests.

The Australia A4 Copy Paper Case (DS529) and the PMS Controversy

The dispute between Indonesia and Australia regarding A4 copy paper (DS529) centered on the highly controversial concept of “Particular Market Situation” (PMS). The Australian Anti-Dumping Commission (ADC) had argued that government intervention in the Indonesian timber sector (specifically the supply of pulp) created a PMS that artificially lowered the cost of paper production. Consequently, the ADC disregarded the actual prices recorded in the financial records of Indonesian exporters and instead used international pulp prices to construct a higher normal value, leading to dumping duties of 30 to 40 percent.

The WTO Panel ruling in 2020 was a significant jurisprudential win for Indonesia. The Panel clarified that the existence of a PMS does not automatically permit an authority to disregard domestic sales prices. Instead, the authority must prove that the PMS prevents a “proper comparison” between the domestic price and the export price. Specifically, if a government policy (such as a raw material subsidy) affects both domestic and export sales equally, it may not create the incomparability required to justify cost surrogation. This ruling effectively closed a loophole that developed nations were increasingly using to target the competitive advantages of developing countries like Indonesia. It also influenced KADI’s approach, ensuring that any future PMS findings by Indonesia are grounded in a rigorous analysis of price effects rather than mere presence of state intervention.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Key WTO Disputes Involving Indonesia

| Dispute ID | Counterparty | Product | Core Legal Conflict | Resolution |

| DS312 | South Korea | Uncoated Paper | Due process and “facts available” | Indonesia Won: KTC revised duties |

| DS529 | Australia | A4 Copy Paper | Particular Market Situation (PMS) | Indonesia Won: ADC revoked duties |

| DS480 | EU | Biodiesel | Cost-adjustment methodology | Indonesia Won: EU removed duties |

| DS618R | EU | Biodiesel | Threat of material injury analysis | Indonesia Won: CVD deemed illegal |

| DS616 | EU | Stainless Steel | Nickel export ban as subsidy | Indonesia Won (2025): EU must revise |

| DS622 | EU | Fatty Acids | Normal value construction (PCN-specific) | Panel Established (April 2025) |

The EU Biodiesel and Stainless Steel Victories (2018–2025)

The ongoing trade friction with the European Union (EU) highlights Indonesia’s strategic focus on protecting its “downstreaming” (hilirisasi) policies. In the biodiesel cases (DS480 and DS536), the WTO repeatedly ruled against the EU’s anti-dumping and countervailing duties. The Panel found that the EU had mischaracterized Indonesia’s Oil Palm Plantation Fund (BPDP) as a government subsidy and had failed to provide objective evidence of material injury to EU producers. The 2025 ruling in case DS618R was particularly devastating for the EU, as it dismantled Brussels’ “threat of injury” analysis, which was found to be based on speculative projections rather than imminent changes in circumstances.

In October 2025, Indonesia secured another landmark victory in the stainless steel dispute (DS616). The WTO Panel concluded that the EU’s countervailing duties on Indonesian stainless steel were inconsistent with the SCM Agreement. Crucially, the Panel ruled that Indonesia’s nickel export policy did not result in raw material prices being set below fair market value and that financial support from Chinese entities to Indonesia’s steel industry did not qualify as prohibited transnational subsidies. This ruling validates Indonesia’s right to use domestic industrial policies to move up the value chain, provided they do not violate specific WTO prohibitions.

Comparative Trade Defense: Indonesia within the ASEAN Context

Indonesia’s trade remedy regime does not exist in a vacuum but is part of a broader regional dynamic within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Indonesia is identified as the most frequent user of safeguard measures among RCEP members, initiating 38 investigations between 1995 and 2021. This preference for safeguards—which target a surge in imports regardless of their source—reflects Indonesia’s historical focus on broad-based protection for sensitive sectors like textiles and steel.

In contrast, Malaysia and Vietnam have historically relied more heavily on anti-dumping measures. Malaysia’s regime, governed by the Countervailing and Anti-Dumping Duties Act 1993, was significantly strengthened in 2025 through amendments that introduced robust anti-circumvention provisions. These measures are designed to target exporters who attempt to bypass duties by rerouting goods through third countries or performing minor assembly operations in Malaysia—a trend that is also being observed in the Indonesian market.

Table 4: Trade Remedy Activity Among RCEP/ASEAN Peers (1995–2021)

| Country | AD Initiations | Safeguard Initiations | CVD Initiations | Primary Strategy |

| Australia | 375 | 0 | 98 | Aggressive AD/CVD |

| Indonesia | 144 | 38 | 0 | Safeguard Leader |

| Malaysia | 109 | 6 | 0 | AD Focused |

| Thailand | 99 | 6 | 0 | AD Focused |

| Vietnam | 32 | 6 | 1 | Emerging User |

| China | 271 | 2 | 14 | Strategic Retaliation |

Vietnam has undergone the most rapid reform, particularly since the enactment of the Law on Management of Foreign Trade 2017. As part of its 2025 legislative overhaul (Resolution 66/2025), Vietnam restructured its court system to establish specialized economic and intellectual property courts, enhancing its capacity to handle complex trade litigation. This regional competition for investment and market share has led to frequent intra-ASEAN trade disputes; for instance, Indonesia has initiated 13 anti-dumping investigations against Malaysia and 10 against Thailand.

2024–2025 Regulatory Frontiers and Strategic Shifts

The 2024–2025 period has marked a decisive shift in Indonesia’s trade policy, influenced by the administration of President Prabowo Subianto. The new government has emphasized “economic sovereignty” and the modernization of the domestic defense and industrial sectors. This has resulted in several regulatory updates that directly or indirectly impact the implementation of anti-dumping law.

Streamlining Non-Tariff Measures (MOTR 16/2025)

In July 2025, the Ministry of Trade issued Regulation Number 16 of 2025 on Import Policy and Provisions, which replaced the previous MOTR 36/2023. This regulation represents a significant effort to streamline non-tariff measures (NTMs) by expanding automatic licensing and shifting from border checks to post-customs clearance inspections. While this reform is intended to improve ease of doing business, it also places a greater burden on KADI and the Directorate General of Customs and Excise to monitor import patterns for potential dumping or circumvention after the goods have entered the domestic market.

Table 5: 2025 Customs and Trade Policy Updates

| Regulation | Effective Date | Core Change | Impact on Trade Defense |

| MOTR 16/2025 | Aug 30, 2025 | Simplification of import licenses | Increased reliance on post-border audits |

| KMK-12/2025 | Nov 13, 2025 | Standardized export units | Improved data accuracy for margin calculations |

| Perpres 110/2025 | Oct 10, 2025 | Revocation of carbon trade moratorium | Potential for “Green” trade defense measures |

| OJK Reg 1/2025 | Jan 10, 2025 | Derivatives reclassified as capital markets | Alignment of trade finance oversight |

| GR 28/2025 | July 2025 | Risk-based business licensing | Streamlined entry for low-risk importers |

The Emergence of Anti-Circumvention as a Priority

One of the most significant challenges facing the Indonesian domestic industry is the practice of circumvention. In 2022 and 2023, KADI observed a surge in imports of steel products from third countries like Thailand and Vietnam, which were allegedly Chinese products rerouted to avoid Indonesian anti-dumping duties. Unlike the United States or Malaysia, Indonesia currently lacks a dedicated, comprehensive anti-circumvention regulation.

However, the finalized EU-Indonesia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) in September 2025 includes specific provisions to tackle circumvention and provides for a “best practices dialogue” on trade remedy enforcement. This is expected to trigger the drafting of new domestic anti-circumvention rules in 2026, which would allow KADI to extend existing duties to slightly modified products or those transshipped through neighboring countries.

The Homo-PP Case and Petrochemical Protectionism

In November 2025, KADI concluded a high-profile investigation into the dumping of Polypropylene Homopolymer (homo-PP) from eight countries, including Vietnam. The investigation, initiated by PT Chandra Asri Pacific, found that foreign exporters were selling homo-PP—a critical raw material for plastics—below fair market value, threatening the survival of Indonesia’s petrochemical downstreaming efforts. This case is indicative of a broader trend where Indonesia uses anti-dumping instruments to protect capital-intensive industries that are vital for its “Golden Indonesia 2045” vision.

Technical and Institutional Challenges in KADI’s Operations

Despite the maturation of the legal framework, KADI continues to face several technical and administrative hurdles that undermine the effectiveness of anti-dumping measures.

- Data Scarcity and Non-Cooperation: Many foreign exporters, particularly those from non-market economies, refuse to participate in KADI investigations or provide misleading information. While KADI can use “facts available,” this often results in conservative duty rates that may not fully offset the dumping injury.

- Lengthy Resolution Timelines: The 12-to-18-month investigative window often means that by the time duties are imposed, the domestic industry has already suffered irreparable harm. There is a growing call for the implementation of “Provisional Measures” earlier in the process to provide immediate relief.

- Transparency in Injury Proving: Several studies indicate persistent problems with the transparency of the methodology used to prove “threat of material injury”. The WTO DS618R ruling against the EU’s speculative injury analysis has set a high bar that KADI must now meet in its own investigations to avoid being challenged.

- Institutional Coordination: The fragmentation of authority between the Ministry of Trade (which investigates) and the Ministry of Finance (which levies the duty) can lead to delays. Furthermore, the lack of a specialized trade court means that appeals must be handled by the Tax Court, which often lacks the expertise to deal with complex WTO law.

Cultural and Ethical Dimensions: Sharia Economic Perspectives

A unique feature of the Indonesian legal discourse is the integration of Sharia economic principles into the analysis of trade practices. In the context of dumping, Sharia law views the practice through the lens of ighraq (predatory pricing) and dharar (harm). Islamic economic thought emphasizes that market competition must be “fair” and that pricing strategies intended to eliminate competitors or create monopolies are fundamentally unjust.

From this perspective, anti-dumping measures are not merely protectionist barriers but are seen as tools of “substantive justice” that protect the broader public welfare (maslahah ‘ammah). This provides a strong social and ethical mandate for the government to maintain a robust trade defense system, framing it as a means of preventing the exploitation of the domestic market by powerful global actors.

Synthesis and Future Outlook

The development of Indonesian anti-dumping law within the WTO framework has been a journey from basic compliance to strategic mastery. The transition from the 1995 Customs Law to the 2025 Import Policy reforms reflects a nation that is increasingly confident in using the tools of international trade law to protect its economic interests. The series of WTO victories against the EU and Australia has validated Indonesia’s “downstreaming” policies and established the country as a leader among developing nations in challenging the discriminatory trade practices of advanced economies.

Looking toward 2026, the Indonesian trade defense regime is expected to focus on three strategic pillars:

- Regulatory Expansion: The drafting of anti-circumvention and transshipment regulations to close loopholes in the current framework.

- Digital and Environmental Integration: The use of standardized digital customs data (KMK-12/2025) and the integration of carbon pricing (Perpres 110/2025) into trade defense calculations, potentially leading to “green” anti-dumping duties.

- Institutional Professionalization: Strengthening the technical capacity of KADI and potentially moving toward a more autonomous trade remedy agency, similar to the models used in the US or the EU.

As Indonesia pursues its “Golden Indonesia 2045” vision, the anti-dumping law will remain a critical instrument for balancing the benefits of global trade with the necessity of maintaining economic sovereignty and industrial resilience. The challenge will be to ensure that these measures remain a corrective tool for unfair trade, rather than becoming a permanent shield for uncompetitive industries. By adhering to the rigorous evidentiary standards of the WTO while aggressively defending its domestic policy space, Indonesia is charting a path that could serve as a model for other emerging economies in the 21st-century global market.

Protect Your Industry! 🛡️ Foreign dumping practices aren’t just a global challenge—they are a direct threat to your business. Under the latest WTO legal framework, your company is entitled to fair protection. Don’t let unfair import competition erode your market share. Consult your defense strategy with the experts at DSAP Law Firm’s Anti-Dumping Services.

Struggling with Import Surges? The evolution of Indonesian anti-dumping law highlights how critical expert legal counsel is during KADI investigations. DSAP Law Firm acts as your strategic partner to ensure your industrial rights are upheld to WTO standards. Contact us now for maximum business protection!